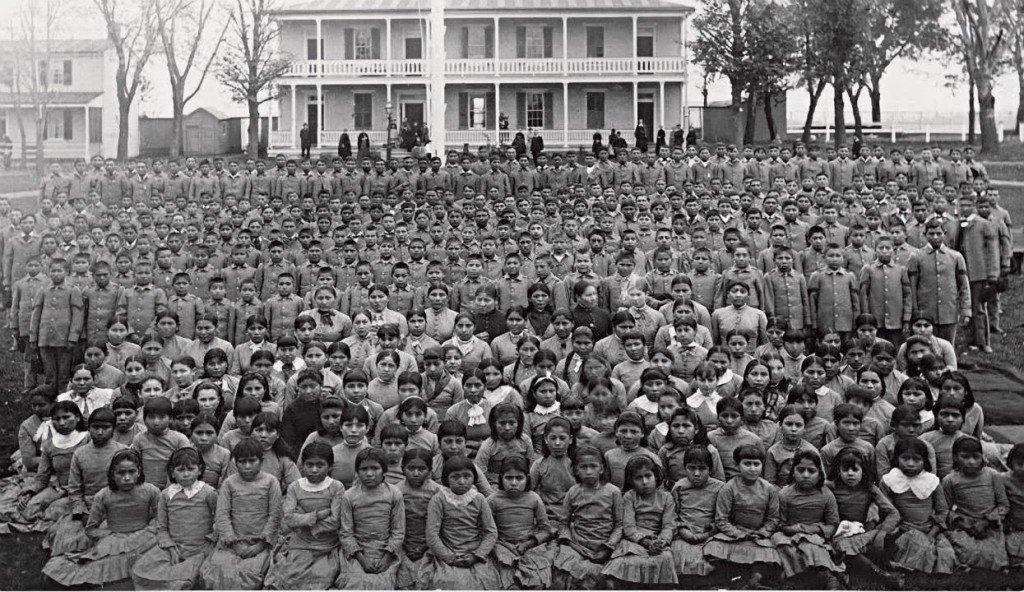

From 1879 to 1910 over ten thousand Native American children from every corner of the United States were sent to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Often thousands of miles from home, the students underwent a program of Americanization. Up top is the sadly un-ironic cover of the school newspaper The Carlisle Arrow and Red Man.

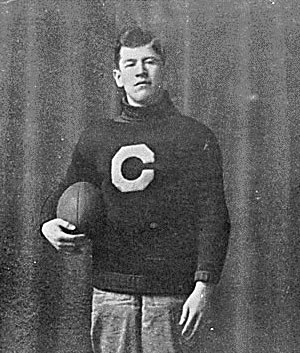

The Carlisle School served as a sorry standard-bearer to an insidiously brutal chapter in relations between Indians and the United States. The curricula was designed to erase the student’s heritage, effectively reprogramming them as whitewashed Americans. School founder Col. Richard Henry Pratt (pictured above) was blunt in describing his philosophy:

A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one. I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him and save the man.

Earlier this year Dickinson College digitized Carlisle’s records and put them online for public scrutiny. The results are a dense and melancholic look into the lives of people who’s cultural identity was stolen from them in their adolescence.

In 1906, a fourteen year old Spokane girl named Lulu O’Hara (third from the left on the bottom row) was sent from Washington State to Carlisle by her grandfather. As evidenced by her records, Lulu was schooled in menial labor like general housework and sewing, earning consistent praise in her reviews. At 17 she was allowed to work as a housemaid in a respectable white household, with a meager wage of $6 per month. Historian Larry Cebula notes on his blog that the process is called “outing” and it:

…reinforced the Carlisle view of the future of American Indians after they graduated, working in either manual trades or as domestic servants.

There were doctors and lawyers that came out of Carlisle but they were the vast minority. Most if not all students contracted some form of debilitating or deadly disease and often students ran away due to fear of death because they were homesick and did not want to die.

In all 186 students would die during their term at Carlisle, a painful reminder that even as late as the early 20th century the native population was often devastated by disease. Today their bodies lay interred in a cemetery on the school grounds. Writer and Indian rights advocate Suzane Shown Harjo argues passionately for the cemetery’s preservation:

Dickinson University has made the Carlisle Indian Industrial School documents available to the public. You can look through them here.